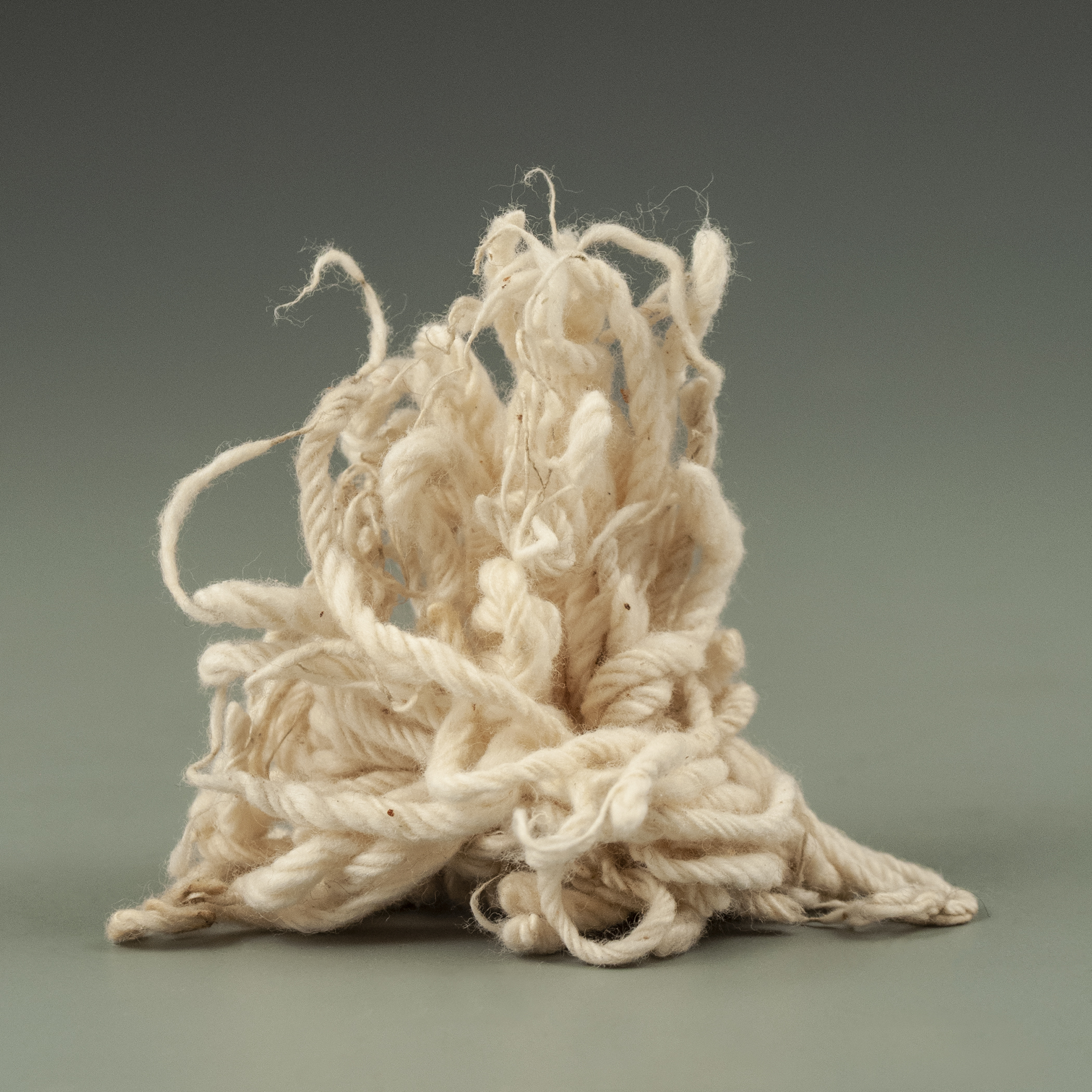

Butter Lamp Wicks

Nepal, 1989

Or so it was, long ago. These days, garish Christmas lights, mass produced in China or India, are draped like curtains over homes and storefronts. Cascades of bright bulbs blanket the entrances of banks and supermarkets, filling the narrow streets of Kathmandu with a manic blaze.

On the night of Laxmi Puja, in November of 1989, I wandered into Asan Tole and Indrachowk, two of the oldest neighborhoods in Kathmandu. The streets were packed. There was a wild, party atmosphere. Powerful firecrackers exploded, dogs ran off in terror, and a million electric lights blinked epileptically above the revelers.

Suddenly, there was a different kind of explosion: A vintage generator, atop a nearby metal pole, shorted out with a shower of blue and red sparks. The streets were plunged into darkness. Everything came to a halt, and a thousand people caught their breath. All one could see, in every direction, were the flames of flickering butter lamps, burning by the doorways and on the window sills of the poorest, most traditional homes.

It was as if a spell had been cast. The lovely rangoli along the street sides—until now ignored, or carelessly trampled—glowed with the light of candles within. There was giggling, whispers, and near-total silence. Even the dogs ventured back to the streets.

And then, without warning, power was restored. The streets and squares were again at the mercy of flashing lights, pulsing Bollywood soundtracks, the sizzle of cherry bomb fuses. But in that last instant—the immeasurable moment after electricity returned but before the melee resumed—I heard a collective sigh of sadness.

These cotton butter lamp wicks were purchased a few minutes later, for about a dime, at a tiny street stall selling lentils, rice, and chilies. They seemed both magical and sad: like the fuses of a broken time machine.